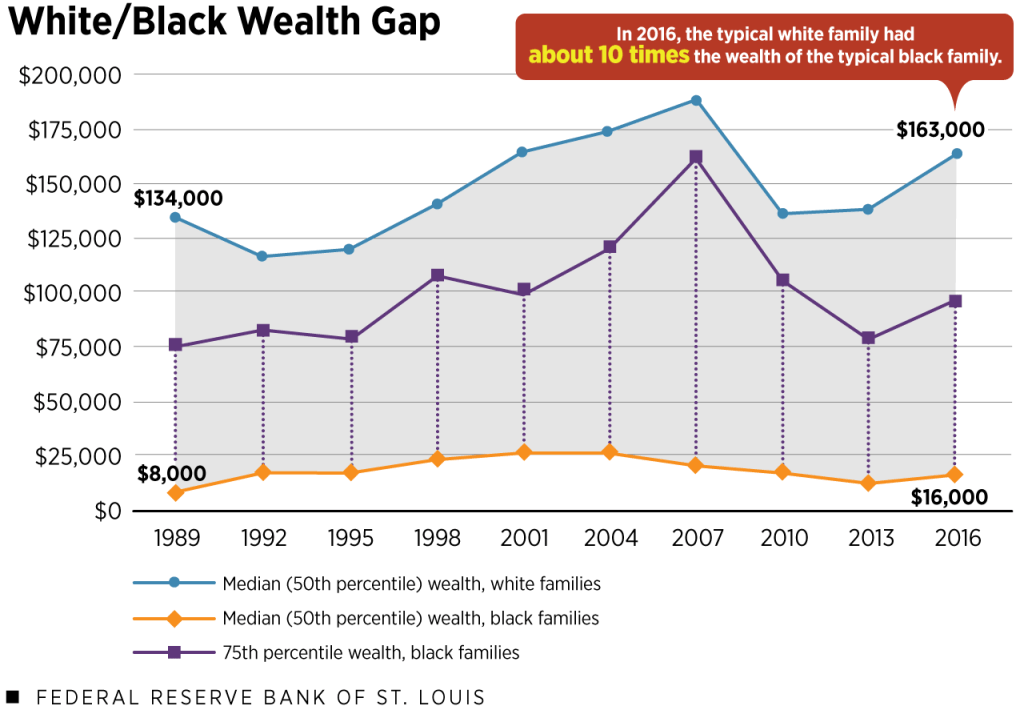

The Black community is eager for revitalization, having long endured economic inequality with the slowest progress toward equity out of any racial group in the United States (Hamilton et al., 2015; DeNavas-Walt and Proctor, 2015)1. Rising above economic inequality is not unknown to the Black community. Before the tragic events of 1921, the Greenwood District in Tulsa, also known as Black Wall Street, was a thriving hub of economic prosperity within the African American community. This area boasted a vibrant entrepreneurial spirit, with over 10,000 residents actively engaged in various business ventures. Community leaders in Greenwood actively promoted economic initiatives and independence, fostering an environment of financial autonomy. The 1920 census documented numerous African-American-owned establishments in the district, including billiard halls, clothing stores, music shops, and more. Additionally, Greenwood was home to essential institutions such as schools, a hospital, and newspapers, highlighting its significance as a self-sustaining community (Messer et al., 2018). Events like the end of Reconstruction and the Tulsa race massacre involved violent acts that robbed Black communities of their progress. Discriminatory policies like redlining and segregation limited opportunities for Black individuals. This history highlights how it took violence and state-sanctioned actions to remove or restrict economic prosperity for Black communities all over the country. However, understanding this history is not discouraging; it’s a call to action. By learning from our past, we empower ourselves to contribute to the ongoing journey of rejuvenation. Economists have a critical role to play in this journey. How do we turn the tides in this historic and ongoing story of economic oppression?

In my research, I study the impact of racism on Black socioeconomic outcomes, how social identities, like race, were formed to create a stratified system, and the ways in which policies uphold a racialized system or work towards racial equity. My drive to become an economist, to solve these problems and revitalize the Black economy, stemmed from witnessing the disparities faced by my family and the broader Black community compared to our white counterparts. This awareness fueled my desire to understand and address these inequalities, guiding my focus towards serving the Black community. Though I didn’t know it at the time, I would eventually come to realize how deep the roots of racial economic inequality go.

The way we fix that is through structural reforms that breathe new life into the local economy, creating jobs, businesses, and opportunities, to improve overall well-being. It’s about making positive changes to uplift the community and address longstanding challenges.

How Do We Revitalize the Economy for the Black Community?

Structural, systemic, and institutional solutions are vital for uprooting racialized structures and healing multi-generational traumas. We must address the roots of the problem, not just the surface. Solutions for Black economic revitalization include:

- Advocate for changes in education to address biases and ensure equitable resources for Black communities.

- Push for legal reform to address racial profiling and unfair sentencing.

- Support initiatives to combat housing discrimination and promote affordable housing.

- Dismantle discriminatory practices in finance and support Black-owned businesses.

- Improve healthcare access and address disparities in Black communities.

- Advocate for policies acknowledging historical injustices and promote economic empowerment through initiatives like reparations.

Black Economics

Early in my Ph.D. program, I noticed a gap between traditional economics and the realities of the Black community. While my goal was to contribute to Black economic revitalization, my initial years felt like indoctrination into a predominantly white perspective of economics, steering me away from this mission. First, the field prioritizes positive economics, which involves analyzing facts and figures to predict outcomes. Personal values, beliefs, and experiences, especially those of marginalized groups like Black women, are often dismissed in positive economic research. Furthermore, traditional economics relies on theoretical assumptions, like, “rational decision-making” and “self-interest,” which don’t always align with the complex factors influencing decisions in the Black community2.

Traditional economics relies on theoretical assumptions like ‘rational decision-making’ and ‘self-interest,’ which don’t always align with the complex factors influencing decisions in the Black community.

Black Americans are systemically affected by wage discrimination, loan discrimination, community disinvestment, limited access to quality education, and life in socioeconomically disadvantaged neighborhoods, among other inequities. Because of these complex factors, Black Americans are operating under fewer opportunities to choose from, lower income and credit sources, lower risk aversion to risky behaviors, less leverage to create advantages for themselves, and lower returns to their investments compared to the average white American. Without understanding these systemic differences across racial groups, it is easy to see how the typical economist could perceive deficiencies within the Black population or attribute choices made by Black individuals as irrational, rather than systematically limited.

These biases and disconnects left me with the impression that I would have to sacrifice my interest in pursuing economic research for the Black community to gain credibility in academia. This large consensus in economics was harmful to me, personally, in my pursuit to join this field, but also to Black economics at large because it sends a “blame the victim” message. This message leads to pursuing solutions that target the victim (i.e., Black Americans) to change their circumstances, rather than solutions that target the perpetrator (i.e., systems, institutions, and laws) to stop victimizing.

The field of economics is lacking in diverse voices, particularly from the Black community, and my early experiences as a Ph.D. student seemed to confirm this. However, my advisor introduced me to a broader literature by Black economists, offering a glimpse into the rich diversity of thought within the field. Leaders like William A. Darity, Jr. and Darrick Hamilton, among others, are conducting research on structural reforms like reparations (Darity Jr. et al., 2022) and the insufficiency of non-structural reforms like desegregation in the education system (Diette et al., 2021), that are critical for Black economic revitalization. Later, I expanded my network beyond the university through organizations like the American Economic Association (AEA) Mentoring Program for underrepresented minorities in economics and The Sadie Collective–which honors the first Black Ph.D. economist, Dr. Sadie T.M. Alexander. I discovered a community of scholars from diverse backgrounds who taught me that there is a space to pursue a form of academic economics that represents the Black community to better understand “Black economics”. These programs not only exposed me to impactful research, but also provided a supportive community that revitalized both my research and mental health. Now, I’m developing my conceptual theory that shows how the unequal socioeconomic outcomes of the average Black American are largely driven by structural barriers, rather than the individual differences in choices and culture that are assumed to be independent of these barriers.

Economic Racism & School Policing

One example of how traditional economic theory falls short of providing solutions to the Black community is in school resource officer policies. A school resource officer (SRO) is a sworn law enforcement officer who is trained in community-oriented policing and serves as school-based law enforcement and crisis responder. SROs are employed by local law enforcement agencies and assigned to work collaboratively with one or more schools. My research on SROs is connected to my goals of Black economic prosperity because SROs impact the economic prosperity of Black communities through increased contact with the criminal/legal system through the school-to-prison pipeline. Also, SROs are publicly funded resources, so more resources go towards SROs, and less money goes to other non-police resources Black communities need for upward mobility. This is particularly true if the school district is sharing in the cost of hosting SROs because that is less education spending on teaching and programming resources that can help increase opportunities for Black students.

During the school desegregation era is when SROs first began moving amongst students, allegedly because of concerns about student and staff safety (Counts et al., 2018; The Center for Public Integrity, 2021). The program then expanded during the war on crime and drugs era, driving police into schools that were predominantly populated by Black students (Advancement Project & Alliance for Educational Justice, 2021). It wasn’t until after the 1999 Columbine High School shooting that SROs began to be placed in suburban white schools in greater prevalence in response to these types of events (Anderson, 2018; The Center for Public Integrity, 2021). Even though SROs have been in place since the 1950s, statutory regulation of SROs didn’t begin until the 1990s and the push to hire better-qualified and better-trained police officers didn’t take off until after 2010, largely driven by concerns about racial disparities related to SROs and other related disproportionalities (Kelley et al., 2022; The Center for Public Integrity, 2021).

Outcomes like suspensions, expulsions, law enforcement referrals, and in-school arrests continue to disproportionately impact students of color in urban geographies.

I argue that the implementation of individually-based reforms to alter the behavior of SROs will not improve Black-white discipline disparities. Outcomes like suspensions, expulsions, law enforcement referrals, and in-school arrests continue to disproportionately impact students of color in urban geographies. Instead, we must identify the structures put in place to serve the purpose of racial stratification, and then target those structures for reform. We need policies that target systemic factors, like the lack of alternative behavioral resources, culturally non-responsive classroom management, and mental stress from exposure to police that Black students are more likely to face than white students.

If I took a traditional economic model that ignores systemic discrimination, individually-based SRO regulations should reduce racial disparities. That is because traditional economic theory assumes the primary way SRO discrimination against Black students occurs is through the direct actions and beliefs of the officers, and not through structural or institutional factors. But when taking a Black economics approach we use the history of how the institutions of education and policing suffer from the legacies of slavery and Jim Crow segregation, as well as local responses to increasing Black populations during the Great Migration, to understand the different conditions Black students face. Considering these structural factors, SRO regulations, without complementary structural reform, cannot be expected to make much of a dent in combating racial inequality in schools. Acknowledging systemic discrimination allows us to better understand why SRO selection and training policies are not effective at reducing racial disparities in school discipline.

Conclusion

As a Black economist, I’m dedicated to challenging these biases and reshaping the narrative to create a more inclusive and equitable economics and economy. Traditional economic perspectives have often overlooked the experiences of the Black community. By understanding the historical context of economics, we can work towards transforming the field into a tool that serves justice and equity for all communities. We know that waiting for the system to act will only continue to leave us behind. Individual actions are also crucial for driving change within the Black community–these are the actions I suggest we follow to reshape our economic future:

- Support Black-owned businesses to foster economic growth.

- Promote financial literacy to empower informed decision-making.

- Volunteer with community organizations focused on social and economic justice.

- Participate in civic engagement activities, including voting and attending community meetings.

- Invest in education and skill development to enhance economic prospects.

- Share information and leverage networks to bridge knowledge gaps.

- Establish mentorship programs to provide guidance and support for personal and professional growth.

I’m committed to producing research that demonstrates the effectiveness of these solutions. By studying and providing evidence for systemic and structural approaches, I aim to show their practical impact. This work is rejuvenating because it breaks away from suppressive ways of thinking and allows me to contribute tangibly to my community, supporting actions for positive change. I want to be an example for future Black economists, especially Black women. The first Black Ph.D. economist was Dr. Sadie T.M. Alexander, and her legacy will continue to hold strong through women, like those of us, in The Sadie Collective. We don’t have to conform to dominating perspectives in economics, often shaped by white and male voices. Economics is powerful, and if we’re passionate about solving community problems, we can bring our unique perspectives to this field and drive impact. We can challenge traditional narratives and lead in creating a more inclusive, diverse, and equitable economy.

References

Advancement Project, & Alliance for Educational Justice. (2021). History of school policing & the school to prison pipeline movement. The National Campaign for Police Free Schools. https://policefreeschools.org/timeline/

Anderson, K. A. (2018). Policing and middle school: An evaluation of a statewide school resource officer policy. Middle Grades Review, 4(2), 1–24.

Asante-Muhammad, D., Sanchez, C., Kamra, E., Ramirez, K., & Tec, R. (2022). Racial wealth snapshot: Native Americans. National Community Reinvestment Coalition. https://ncrc.org/racial-wealth-snapshot-native-americans/

Counts, J., Randall, K. N., Ryan, J. B., & Katsiyannis, A. (2018). School resource officers in public schools: A national review. Education and Treatment of Children, 41(4), 405–430. https://doi.org/10.1353/etc.2018.0023

Darity Jr., W., Mullen, A. K., & Slaughter, M. (2022). The cumulative costs of racism and the bill for Black reparations. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 36(2), 99–122. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.36.2.99

DeNavas-Walt, C., & Proctor, B. D. (2015). Income and poverty in the United States: 2014. In Current Population Reports (Issues P60-252). U.S. Government Printing Office. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2014/demo/p60-249.pdf

Diette, T. M., Hamilton, D., Goldsmith, A. H., & Darity Jr., W. A. (2021). Does the Negro need separate schools? A retrospective analysis of the racial composition of schools and Black adult academic and economic success. RSF: Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences, 7(1), 166–186. https://doi.org/10.7758/RSF.2021.7.1.10

Hamilton, D., Darity Jr., W., Price, A. E., Sridharan, V., & Tippett, R. (2015). Umbrellas don’t make it rain: Why studying and working hard isn’t enough for Black Americans. In Insight Center for Community Economic Development (Issue April).

Human Rights Watch [@hrw]. In the span of about 24 hours between May 31 and June 1, 1921, a white mob descended on Greenwood [Video embedded] [Post]. X. https://twitter.com/hrw/status/1267133235600986117

Kelley, B., Brown, D., Peisach, L., & Perez Jr., Z. (2022). K-12 school safety 2022: School resource officers. Education Commission of the States. https://reports.ecs.org/comparisons/k-12-school-safety-2022-05

Messer, C. M., Shriver, T. E., & Adams, A. E. (2018). The destruction of Black Wall Street: Tulsa’s 1921 riot and the eradication of accumulated wealth. American Journal of Economics and Sociology, 77(3/4), 789–819. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajes.12225

Robertson, C., Searcey, D., & Oppel Jr., R. A. (2021, May 24). The 1921 Tulsa race massacre: A visual history. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2021/05/24/us/tulsa-race-massacre.html

The Center for Public Integrity. (2021). The history of school policing. The Center for Public Integrity. https://publicintegrity.org/education/criminalizing-kids/the-history-of-school-policing/

Tulsa Historical Society & Museum. (n.d.). 1921 Tulsa race massacre. https://www.tulsahistory.org/exhibit/1921-tulsa-race-massacre/

Endnotes

- The Indigenous community has also experienced slow progress, slower than the Black community in some socioeconomic indicators, but slightly ahead of Black Americans in wealth and homeownership (Asante-Muhammad et al. 2022). ↩︎

- Rational individuals are defined as having well-defined goals and trying to fulfill those goals the best they can. Self-interest refers to the idea that individuals are only interested in their gain, and making decisions to pursue those. ↩︎