I

n the dream, I am standing on a lawn that stretches to a wood line. It looks like the fields in my hometown in rural Michigan. The bag of seed in my right hand is heavy and the sky is bright blue like in the summers of my childhood. There is a small flock of baby chicks in front of me, maybe a dozen, pecking in the short grass. My Ojibwemowin teacher Zoe is standing behind me, she too has a heavy seed bag in her hand. She smiles at me, and looks down. I look towards the chicks again, and say the word ozaawizi, h/ is brown1, and point at them, their yellow and brown fuzz gleaming in the sunlight. Zoe smiles at me again.

I wake up in the spare bedroom of my parent’s home and cry–after three months of learning Ojibwemowin I have had my first dream in it. It took four years before I had my first dream in French. This is the most important thing that has happened to me since I began graduate school.

I am a citizen of the Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians, bear clan, and descendant of Indian Boarding School survivors. I was never supposed to have this language, Ojibwemowin, it was stolen out of the mouth of my ancestors in the Catholic Indian Boarding Schools in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. My grandmother was the last one to be fluent in Ojibwemowin. My father only speaks English. He tells me he used to hear his mother occasionally “talk Indian” on the phone to her siblings, and when they visited family up north. He never learned it, it was not spoken around him consistently enough for him to pick it up. This is unsurprising–my grandmother had moved all the way down state to Detroit to give her children better lives. Why would speaking Ojibwemowin to her children be of importance in the city, after generations of her family had been taught to not speak it from boarding schools?

I am enrolled in the History department at the University of Minnesota to earn a Ph.D. on research of Native activism in the 1970s in Detroit, specifically revolving around a local community center and Native-run newspaper. In particular, I am researching the way that Native people and especially Native women in Detroit maintained and created Native identity for themselves and their relatives, especially their children. I am doing it because us living relatives need to learn from those women in Detroit who were resisting colonization of their minds and bodies and children and homelands in the 1970s in the same way myself and all my relatives need to learn how to resist now. This research starts with learning how to speak and think in Ojibwemowin, because that is the language my grandmother and the women she lived around thought through their resistance in. I cannot resist in English effectively anymore. This is the oppressor’s language, it does not work well enough for my means anymore–I have resisted all I can with the oppressors tools, and the house is still not dismantled.2

This research starts with learning how to speak and think in Ojibwemowin, because that is the language my grandmother and the women she lived around thought through their resistance in.

With that, my role as a “Historian” is complicated–it is a word warped with colonial meaning. I think of my work in a variety of ways–it is ceremony, it is healing, it is care, it is love, it is reclamation, it is rematriation, it is the work Native women have always done3. I am pursuing this degree to get closer to my grandmother, a woman I never met. She passed on due to breast cancer in her early 40s, a fact of life for many Native women, who suffer the highest death rate of breast cancer of any population in the United States.4 She lived her life so I could live mine.

There is a concept in Indigenous Feminism, but really it is present in all aspects of Indigenous relationality, that one’s life is not their own. My life is not mine, my life is to be lived in relation to all of my relatives, human and more-than-human. It belongs to the past and to the future, to call it mine would be selfish beyond belief.

I wish I could tell you this in Ojibwe, it doesn’t make sense in English. It sounds silly in English. “This is the oppressor’s language yet I need it to talk to you.5”

In the past year, I have been closely considering how to go about my dissertation research. I had found copies of a Native-run newspaper in an archive, and its articles showed the underrepresented role Native women played in maintaining their broader Native community, including their families and specifically their children’s identity as proud Native people, given the amount of women organizers involved in publishing these papers. To dig deeper into this, I knew I needed to do oral histories with people from the community. Furthermore, I knew that I needed to learn Ojibwemowin in order to ethically do oral histories, as the language would guide me in relations and ethics in a way English cannot.

Learning Ojibwemowin has radically altered my worldview. Having only known English and French, my thoughts were restricted to those possible in the colonizer’s language. I have learned that to speak and think in Ojibwemowin is to be a good relative. I am not, by any means, fluent in Ojibwemowin and I want to say a clear and loud chi-miigwetch to my teacher Zoe Brown and others who have helped me on my journey to learn some of the language. This will be a skill I will work towards for the rest of my life, and it is an honor, privilege, and duty to be able to do so.

Something that remains prevalent in my mind when considering how my research ethics are housed in Ojibwemowin is the fact that Ojibwemowin is a verb based language that focuses on the relationality between the speaker and the relatives around them. I cannot talk about someone without making it clear who they are to me. When we speak of a relative, our relation to them is evident in a single word. Nokomis–my grandmother, specifically my grandmother. I cannot just say “grandmother” standing alone–a grandmother is always in relation to someone. With this in mind, it is so much easier to feel my human and more-than-human relatives around me–I cannot dismiss them into objecthood the way English does.

Nokomis–my grandmother, specifically my grandmother. I cannot just say “grandmother” standing alone–a grandmother is always in relation to someone. With this in mind, it is so much easier to feel my human and more-than-human relatives around me–I cannot dismiss them into objecthood the way English does.

I have a friend who is also an Ojibwekwe, an Ojibwe woman, from another tribal nation in Michigan. She writes about food sovereignty and how our ancestors send their knowledges to us–she taught me the word aanikoobijigan, which means a great-grandparent as well as great-grandchild. The words are one in the same, and the root of the word relates to the way that time is tied together through our ancestors and future ancestors. My thoughts drift back to the word aanikoobijigan again and again, it is a sigh of relief and a balm to the pains of colonialism. I did not know my grandmother, but I know she is just a bit behind me, and my future ancestors are just ahead of me. I am not nearly so lonely as I sit with this word, all of my ancestors are around me, all thinking and speaking Ojibwemowin.

Endnotes

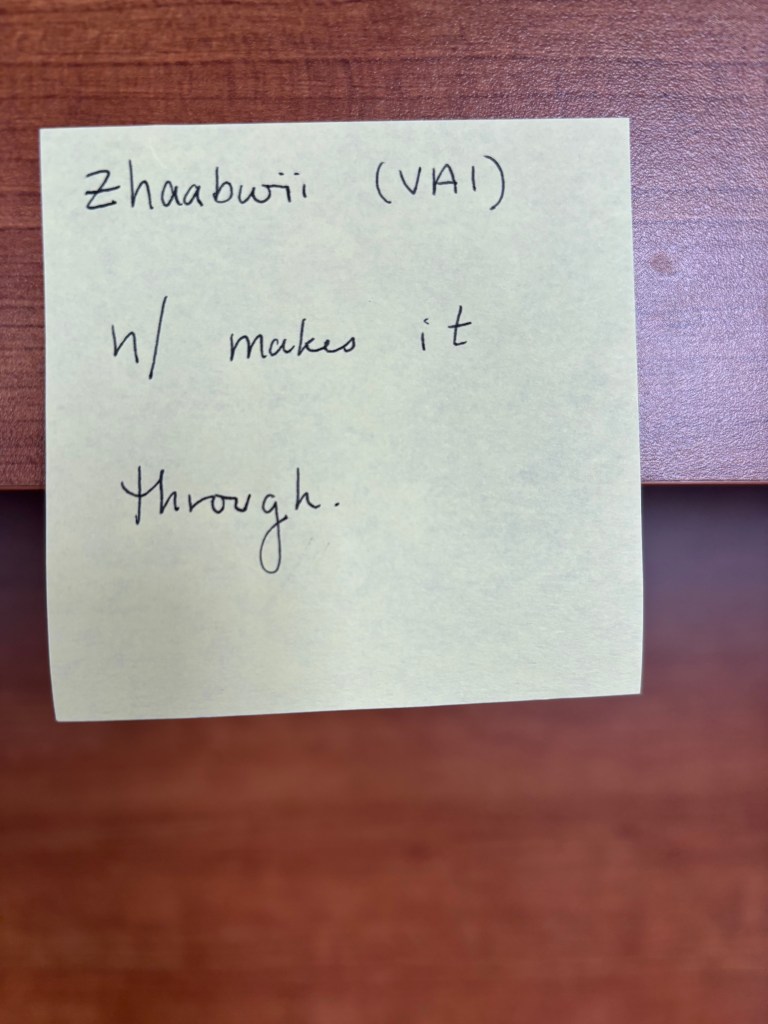

- In Ojibwemowin, there are no gendered pronouns. In my classes, the use of “h/” is often used to represent the genderless singular pronoun “wiin.” I refrain from either using “she/he” or “s/he” or singular “they” as all of these carry with them a variety of connotations from English. Rather than the inclusion of only two genders, or an intentional removal of gender, “wiin” and its English counterpart “h/” are both inherently genderless. ↩︎

- Audre Lorde, The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House. Penguin Books Limited, 2018. ↩︎

- Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, As We Have Always Done: Indigenous Freedom through Radical Resistance, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2017. ↩︎

- Health, Tribal. “Breast Cancer in Native American Women.” Tribal Health, October 1, 2024. https://tribalhealth.com/breast-cancer/. ↩︎

- Adrienne Rich, “The Burning of Paper Instead of Children,” Poetry Society of America, accessed February 13, 2024, https://poetrysociety.org/poems/the-burning-of-paper-instead-of-children. ↩︎