Finding My Voice as a Hmong Woman and Creating Space in Science

Everyone’s journey through science is different. For some, it is about discovery or building a skillset to ensure a promising career. For me, it is about unlearning the gender roles of my culture and finding my voice as a Hmong woman in science.

The origins of my upbringing are rooted in scarcity and oppression, yet incredible strength and resilience. The Hmong people are an ethnic minority from China. However, genocide and marginalization drove much of the population to Southeast Asian countries like Laos, which was where my family settled generations ago. But in 1975, my grandparents and my mother fled from Laos to Thailand to escape the violent aftermath of the Secret War. All they had were the clothes on their backs and a few belongings. On the brink of starvation, my grandmother had to trade two coins from her traditional coin belt—a wedding gift from her parents—to buy a ration of rice, no bigger than the size of a fist, for the three of them to share. She did this every day until the coins were gone. Fortunately, they were rehomed in a refugee camp, and shortly after, received approval to come to the United States.

Like many refugee families, my parents and grandparents taught me all they ever knew: survival and the Hmong culture. My grandparents restarted their lives by working in factory assembly lines, sorting fish, and packing pickle jars until their hands were numb. Both of my parents assimilated into American life, and would later start a family, working long hours to provide for us. This was their American dream. Having a roof over their heads and hot food on the table was more than they could ask for. As a Hmong American child, I am nothing but grateful for their sacrifices. With education and opportunities at my fingertips, I was pushed to pursue a career in law or medicine. These safe and communal professions are prime examples of success for our refugee parents—careers that educate us Hmong children to make a difference in our community. But at its core, this pressure comes from a place of survival where financial security, respect, and social status are guaranteed.

My path to research was by accident. When I started at a community college, I was interested in science, but my feelings while taking classes were of being lost and guideless. I had little clue where a prospective science degree could lead me if I didn’t pursue healthcare. Research was a way to strengthen my medical school application—however, the more time I spent engaged in scientific research, the more my enjoyment and curiosity grew. Yet, I still didn’t know what a career in science looked like. My experience, unfortunately, mirrors many Hmong students who enjoy the sciences, but lack the resources and exposure to STEM careers—fields that are largely underrepresented by Hmong and Southeast Asian minorities. Despite the uncertainties, I took advantage of every opportunity that would equip me with the necessary tools for a long academic ride.

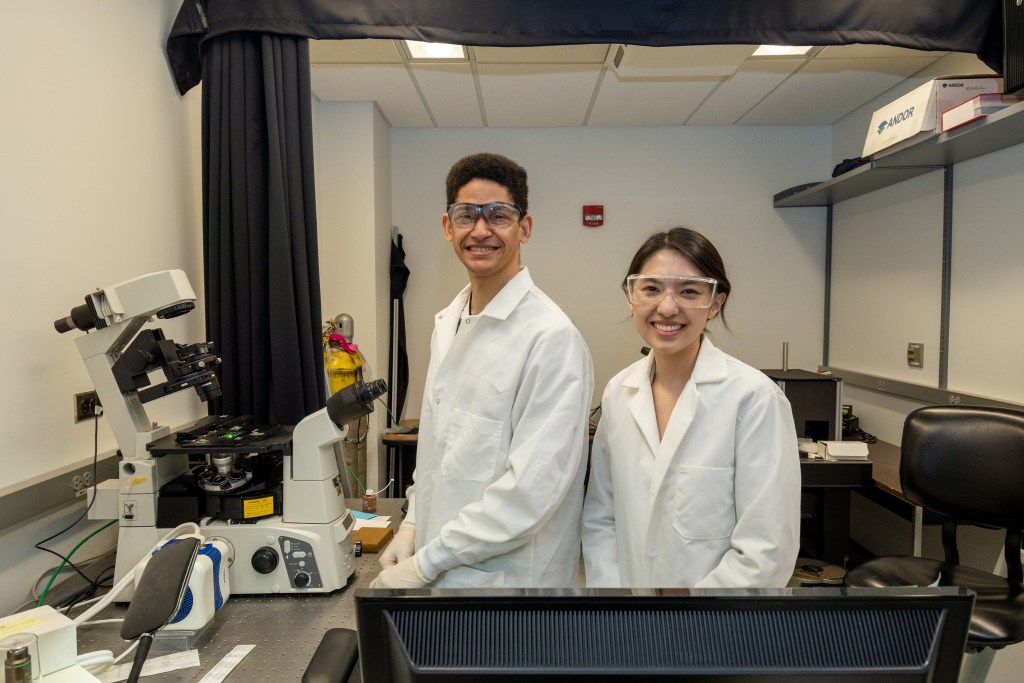

Four years post-graduation, I was still working as a research technician with my sights on medical school when my research advisor asked me a simple question that changed my entire career trajectory: “Have you ever considered going to graduate school?” The answer was no. The thought of breaking away from the norm of a “safe” profession was frightening. But this simple question began broadening a horizon of opportunities I saw for myself. I took my chances, applied to one program, and was thankfully accepted. Currently, I am a third year Ph.D. candidate in the Molecular, Cellular, Developmental Biology & Genetics program. My research aims to understand how myosin VI, a molecular motor protein, is involved in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) progression. My days are spent performing in vitro protein assays and cell-based experiments to dissect the mechanism of function of myosin VI and how it transports overexpressed receptors in PDAC. Fluorescence microscopy is an essential component of my routine to help visualize these cellular events.

But before I learned how to be a student or a scientist, I had to learn how to be a Hmong girl. A demure and obedient daughter who is skillful at household chores brings much respect to her Hmong family, second to having a high education—I was raised to fit the standard of a “good daughter.” That’s because a traditional good daughter will eventually become a good wife to a husband and pleasant daughter-in-law to his family. As the oldest of six children, I was taught from a young age to always care for others, to look presentable, and to be mindful of how others perceive me. It was ingrained in me to keep my head down, work hard, and not speak out of line or question authority, whether it was at home or in the workforce. As a daughter, I am perceived more as a helpful figure within the family rather than a leader who will uphold the clan name, like my Hmong brothers. Still—today, only Hmong men are allowed to sit at discussion tables during weddings and traditional celebrations, while the women cook and serve food. Afterwards, it’s the women that clean the tables and dishes when the celebration is over. I have many memories of helping in the kitchen or clearing tables as a young girl. And even as a woman, I am still helping alongside my mother, aunts, and female cousins whenever there is a family gathering.

Choosing a career in scientific research has broken all expectations of what I was taught a Hmong girl should be. Our voice is our biggest asset in science. We are trained to openly critique, to challenge ideas, and to think independently. As experts in our respective fields, we are continuously sharing our research to audiences at meetings and seeking ways we can push the boundaries of discovery. My experience as a scientist was as much about learning molecular biology as it was about unlearning the gender beliefs I grew up with. It was difficult and uncomfortable for me to use my voice during discussions and to practice independent thinking, some of which are the most important skills in research. The intense nature of research and graduate school inevitably forced me to quickly break these barriers. Science became a way for me to confront my weaknesses. It was painful but vital for my growth, and overtime I have gained immense confidence in my voice and my abilities by doing research. At times, I feel like a different person after having shed so much of my old skin. However, I am still learning every day because I cannot change where I came from, and that’s okay. Despite being raised to fit a box, there are certain attributes as a Hmong woman that make me a strong scientist. Perseverance helps me overcome unexpected hardships and failures. I recognize my ability to be personable and to easily connect with others. I value community and therefore create a positive environment wherever I am. Knowing that I can make an impact, whether big or small, through my work as a scientist is what motivates me to keep going every day.

My experience as a scientist was as much about learning molecular biology as it was about unlearning the gender beliefs I grew up with.

I occupy a space our ancestors don’t have the words for. In the Hmong language, we have no words for science or biology. Even now I cannot communicate with my grandmother and my elders about my work, despite speaking fluent Hmong. This gap in modern vocabulary reminds me how far we have come in just two generations as a marginalized ethnic group, and how much further we have yet to advance in our prosperous new home. For the first time since embarking into research, I have met a handful of Hmong scientists across the country who share similar experiences and motivation in STEM outreach. It is powerful knowing we are the first generation of Hmong scientists and that we are not alone in our aspirations. In 2023, we founded the Hmong Association for Scientific Research with hopes to support Hmong and underrepresented minorities in research across all career levels.

I believe we inherently have many layers to our identity, each one coloring our world a little differently than those around us. That uniqueness is what makes us who we are. I hold no judgment against my elders and my culture for what I was taught. I wholeheartedly embrace my roots and am extremely proud of my heritage. My parents and grandparents, like the generations before them, have passed their knowledge onto me with good intentions, which were the qualities that made a Hmong woman irreplaceable in the community during their times. A Hmong woman needed to have an unwavering willpower to accomplish any task thrown her way. She had to be reliable and altruistic to hold the family and community together. Throughout our history, a Hmong woman’s strength has always been quiet and unseen. But in this generation, we have to be a new kind of Hmong woman to succeed. Not better, but just different, to allow us to adapt and fulfill the goals of what we want in life. Right now, Hmong women are more educated than ever. We can choose to sit at any table that has been historically occupied by men. Having a seat at the table for us means we can create space and invite the next person to join.

In this generation, we have to be a new kind of Hmong woman to succeed. Not better, but just different, to allow us to adapt and fulfill the goals of what we want in life.